Many thousands of miles from home, Keith Davis vanished while at sea. His remains were never located. The circumstances surrounding his untimely demise have now revealed a previously unknown facet of maritime life.

This unsettling disappearance of a fisheries observer sparks questions about safety on the high seas and the fate of the fish stocks observers attempt to monitor.

Let’s deep dive into this mysterious story and unfold past scenarios to understand what happened and what’s happening.

Who was Keith Davis? What did he do?

Keith Davis was a marine biologist who worked as a fisheries observer, a role that is not widely known but is frequently fraught with high levels of danger and excitement.

In 1999, Davis was hired as an observer for the first time in Alaska. He had a degree in biology from college and was drawn to the ocean and the unstructured freedom of observing life. He would labor for long stretches of time before taking months off to travel or return to Arizona, where he was constructing a home next to his father.

He, too, had a compulsive wanderlust, visiting places like Nepal and South America. He raised US $2,000 after the 2015 earthquake in Nepal to aid in the reconstruction of a school there.

He once revealed to a buddy his intention to walk across Israel in support of world peace.

Such goals weren’t unrealistic for Davis; rather, they were justifiable objectives.

Davis’s idealistic side found a professional home in his efforts to safeguard the oceans around the world.

Our eyes and ears on the oceans are the estimated 2,500 observers.

They spend months at a time living on fishing boats as they travel hundreds of miles offshore to preserve those seas from overfishing and gather data that will aid in our understanding of the condition of our oceans and marine life.

Davis was curious about everything—from the dolphins and birds he spotted on the ship to the people he met on far-flung Pacific islands to the flickering silence of the night sky. He would frequently relax on the deck while reading, writing in his notebook, or playing the ukulele.

His friend and coworker Anik Clemens described him as being highly impetuous, amorous, and spontaneous. He had such a zest for what he did. He desired to safeguard both the waters and the fishing industry, as well as the fishermen themselves.

The hard choice that observers were forced to make particularly disturbed him: should he and his coworkers report violent and intimidating incidents—many of which could never be substantiated back on land—when doing so may endanger their safety in dangerous environments?

What happened to Keith Davis?

Hundreds of kilometers from the coast of Ecuador in 2015, a 41-year-old man disappeared during what seemed to be a typical journey aboard the Victoria 168, a tuna fleet owned by a Taiwanese business.

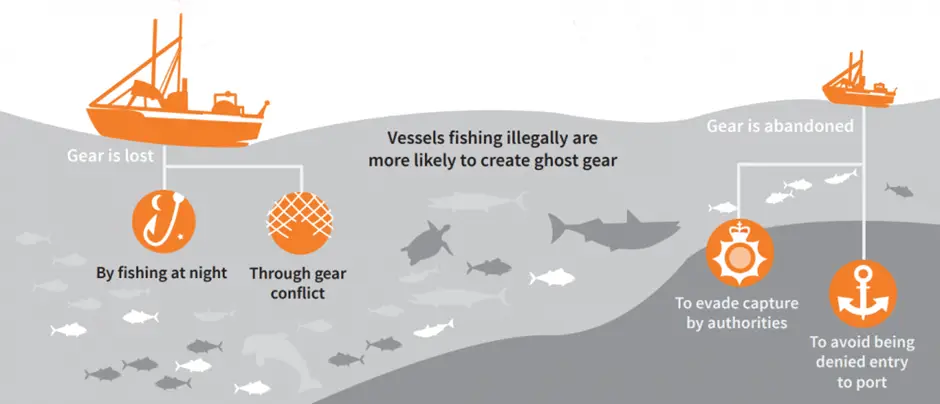

With her vast refrigerated holds, the Victoria served as a tuna transshipment vessel, a mother ship for smaller commercial boats that could unload their catches at sea rather than making frequent voyages back to port.

This setup is also conducive to the smuggling of drugs and shark fins into countries without proper oversight. Davis understood from experience that working as an observer on transshipment vessels was extremely risky.

Transshipment or transshipment is the shipment of goods or containers to an intermediate destination, then to another destination. One possible reason for transshipment is to change the means of transport during the journey, known as transloading.

An excellent example of a transshipment would be the transport from Durban to Manila because there is no direct connection between the two ports.

The crew searched the ship, but they could not find him. His friends and coworkers on the mainland were informed of his disappearance, and many of them were suspicious right once.

The logical conclusion is that he had to have some sort of traumatic event. Perhaps what he observed was something the other passengers on the ship preferred he not see.

What, though, would Davis have seen that might have endangered him? The high seas are known for illegal activity, such as trafficking in drugs, weapons, and occasionally even human beings, because there is minimal control, and legal jurisdiction is complicated there.

To be clear, we haven’t found any evidence that Davis was there for any of those events on the Victoria 168.

The transshipment vessels deliver fresh supplies to the longliner tuna fishing boats and deliver the recently caught fish back to land.

This procedure enables certain tuna long liners to remain at sea for years at a time, which can reduce costs and make it possible for me to buy that 99-cent can of tuna I saw on the shelf of my grocery store.

People who are on the scene of unlawful conduct are extremely vulnerable. The captain’s computer served as Davis’ sole means of communication with the land while he was working on the Victoria 168.

In the event that they see something too delicate to mention aloud, those performing his job may be instructed to converse in code. Although Davis cherished his role as an observer, he was also keenly aware of its risks.

The year before he vanished, he posted on Facebook, “Many of us who have served have witnessed gun activity, knife battles, slavery… much of which we have to swallow as “part of the job.”

Community reaction and battling overfishing

Even compared to Davis, most of these instances receive much less attention. This is because of the fact that many observers are Pacific Islanders who are trying to support their families rather than daring American males like Davis.

They frequently come from areas where artisanal fishing has a long history. This localized economy has frequently been decimated by the entry of transshipment-dependent, globally integrated fishing fleets.

Men who died in mysterious circumstances, like Papua New Guinean observer Charlie Lasisi or Eritrean Aati Kaierua from Kiribas, didn’t make headlines. But the burden of our desire to purchase inexpensive tuna falls primarily on observers like these.

Where did Keith Davis go missing, and the investigation of the matter?

Ten days after Davis vanished, the Victoria returned to the dock in Panama. Panamanian investigators and Berkow’s crew, along with two representatives from MRAG Americas, searched the boat, which is about the size of five and a half semi-trailers.

They searched for any hints as to what might have happened to Davis for eight hours. They discovered his survival suit, which had his emergency beacon and his life jacket inside his cabin.

There wasn’t a lot of information. Davis’s case started to appear like a genuine mystery when Berkow thought about the little evidence back in the United States. He was aware that Davis was a skilled watcher and that he vanished in broad daylight on a quiet day.

These are the facts, according to Berkow. Beyond that, the only information available to investigators was a jumble of speculations, opinions, and conjectures culled from persons who knew Davis and the kinds of circumstances he would have run into at sea.

Davis’s case stood out in Berkow’s 40-year tenure as a criminal investigator. He had previously dealt with cases involving people who went missing at sea while working for the coast guard, but many of them were made up of criminals attempting to dodge the police.

Berkow was frustrated by the difficulty of the situation and lack of control over the investigation because he had never before searched for a missing observer thus far out in the ocean.

The sheer diversity of the concerned nationalities was the first, leading to a host of legal and diplomatic challenges: Despite the fact that Davis was an American citizen, the US Coast Guard was unable to undertake its own investigation since the boat’s registration was in Panama.

Berkow’s team members were allowed to observe interviews but were not allowed to ask any questions.

The potential crime scene was located far away in the Pacific, and the time it took Victoria to arrive at port allowed plenty of time for any evidence to be destroyed and for anyone on board who may have witnessed something to fabricate a story.

In addition, many of the standard investigative techniques were less effective given the circumstances. Additionally, it was challenging to get information from the crew because many of them could not understand English or Spanish.

Davis’s body has yet to be located. FBI and Panamanian officials both conducted fruitless investigations. Davis’s cause of death is now unknown, whether it was an accident, a suicide, or murder.

We do, however, know that a large portion of unlawful behavior at sea relies on the notion that what occurs far from land, where there are no cell phone signals or security cameras, is practically invisible to those of us on the mainland.

They may be susceptible because part of their duty is to watch what takes place at sea.

Our marine world and illegal fishing –

The vastness of the oceans across the Earth cannot be understood simply. Over 70% of the Earth’s surface, or 362 million square kilometers, is covered by them.

However, only a small portion of that is truly under the sovereignty of national governments, whose control over natural resources only extends 370 kilometers beyond a coastal state’s coastline. In other words, water that belongs to everyone and to no one covers more than 40% of the planet’s surface.

Lawlessness is prevalent on the high seas, which is no coincidence.

More than 816 kilograms of wild fish are illegally captured at sea every second, largely in so-called “international waters” that are outside of national borders; this is equivalent to bringing in 211 fully loaded Boeing 747s per day.

Despite the fact that commercial fishing has grown to be a multibillion-dollar industry, fishermen must work harder than ever to fill their nets as fish stocks around the world are depleting, necessitating longer, more expensive voyages.

Many fishermen feel pressured to disobey the numerous laws and standards that govern the commercial fishing industry because the financial stakes are so high.

Ninety percent of the world’s fish supplies are fully or overexploited, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, which highlights the staggering effects of “illegal, unreported, and unregulated” (or IUU) fishing.

As much as 30% of the seafood consumed worldwide is currently caught illegally, unreported, and unintentionally (IUU), bringing in $10 to $30 billion a year and fueling a variety of despicable activities such as human trafficking, environmental destruction, labor abuses, and environmental corruption.

Davis participated in this environment first-hand as an observer aboard fishing boats all around the world, frequently in international waters.

The first observer programs began in the 1950s, and today there are more than 50 across the world, the majority of which are managed by contractors that hire observers on behalf of governments and regional fisheries management organizations (groups of countries that share jurisdiction over a part of the ocean).

Although observers cannot stop or punish illegal activity, their work is crucial for protecting the oceans by giving resource managers unbiased data about fish stocks that they may use to determine fishing quotas.

Ending notes-

His sense of wonder about the world—especially the birds, which he wrote about in an essay—seemed to be captured by the ocean. He described them as “such solitary people,” leading adventurous lives at sea.

He would observe them as they sailed along unseen wind currents hundreds of kilometers away from the nearest piece of land until they were engulfed by the sky.

By paying keen attention to stories like Keith Davis’s and by learning about what happens out on the high seas, we can make things safer for observers, for crews, and our oceans.

Let us remember Keith as an observer, a biologist who took on the duty of observing fisheries around the world to report on compliance, safety, and more. A man who wanted to protect the ocean for us all.