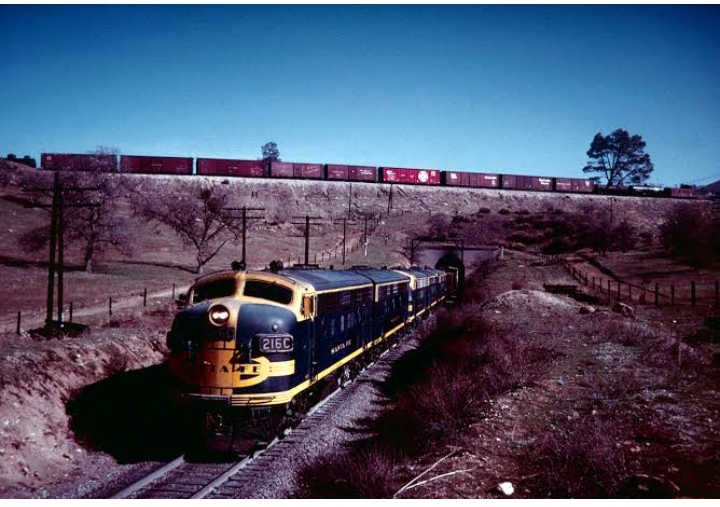

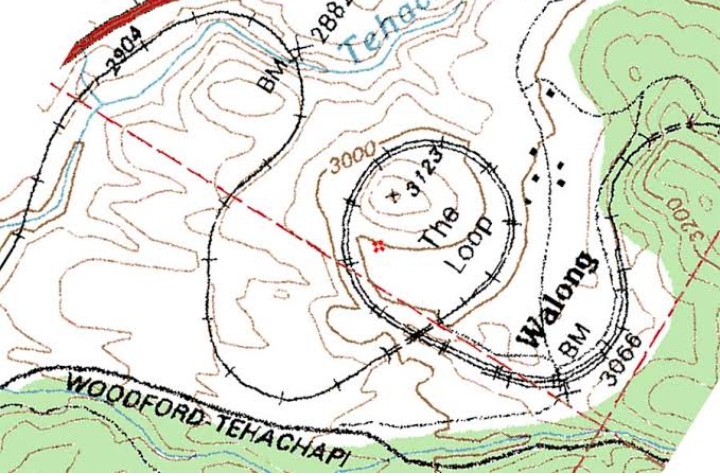

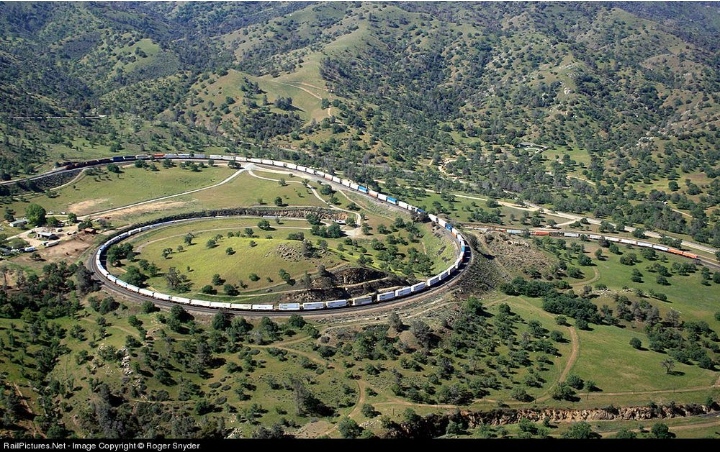

The Tehachapi Loop is a 3,779-foot (0.72-mile; 1.15-kilometer) long spiral or helix that runs along the Union Pacific Railroad Mojave Subdivision in Kern County, south-central California, via Tehachapi Pass. The line connects Mojave in the Mojave Desert with Bakersfield and the San Joaquin Valley.

The track gains 77 feet (23 m) of height and forms a circular 1,210-foot (370 m) diameter while rising at a constant two percent slope.

To complete the Loop, any train that is at least 3,800 feet (1,162 m) long (about 56 60′(67’11”) box cars) crosses over itself.

The train travels through Tunnel 9, the ninth tunnel constructed as the railroad was expanded from Bakersfield, at the bottom of the Loop. The Southern Pacific Railroad constructed the Loop, one of the most outstanding engineering achievements of its day, to reduce the grade across Tehachapi Pass. The line opened in 1876 after construction started in 1874. William Hood, the project’s principal engineer, and Arthur De Wint Foote both contributed to its construction

In honor of Southern Pacific District Roadmaster W. A. Long, the siding on the Loop is referred to as Walong.

The Loop was the first of its sort when it was finished in 1876. According to the historical monument put up in 1953 when the Loop was named a California Historic Landmark, it is now regarded as “one of the seven marvels of the railroad world.” A little more than 30 years later, in 1998, the American Society of Civil Engineers classified the Loop as a National Civil Engineering Historic Landmark (ASCE).

Under the direction of James R. Strobridge and William Hood, civil engineers for Southern Pacific, the project was built using a labor force that was predominately Chinese. To refuel steam locomotives, the Tehachapi route required 18 tunnels, 10 bridges, and numerous water towers. To create the helix-shaped, 0.72-mile (1.16 km) Loop between 1875 and 1876, roughly 3,000 Chinese laborers used only hand tools, picks, shovels, horse-drawn carts, and blasting powder. The gradient of the terrain averaged about 2.2 percent, with an elevation rise of 77 feet (23 m). With the assistance of 8,000 Chinese laborers employed by Strobridge and another individual, the railway was extended through Southern California and the Mojave Desert in 1882.

The Cross at the Loop, a big white cross, is perched atop the hill in the Loop’s middle in honor of the two Southern Pacific Railroad workers who died in San Bernardino, California, on May 12, 1989, in a train derailment. The surrounding town of Tehachapi is home to the Tehachapi Depot Museum.

When the Union Pacific and Southern Pacific railroad systems amalgamated in 1996, The Loop was transferred to the Union Pacific Railroad. The BNSF Railway also has trackage rights to use the Loop for their trains.

Despite operating passenger trains on the Loop for years, Southern Pacific quickly stopped doing so after turning over control of its trains to Amtrak in 1971. Since Union Pacific acquired Southern Pacific, the restriction has been in place. Amtrak’s San Joaquin train cannot immediately serve Los Angeles. Amtrak runs Thruway Motorcoach buses for travelers who want to travel from the Central Valley to Los Angeles, and Amtrak runs Thruway Motorcoach buses.

BNSF has trackage rights even though Union Pacific is the actual owner of the railroad following the completion of its 1996 acquisition of Southern Pacific. According to various sources, it is used by anywhere from 30 to 50 freight trains every day.

Due to this high traffic volume, Union Pacific, BNSF, and Caltrans collaborated to upgrade the line in 2013 with sections of double-tracking and improved siding. The modifications, which started in 2014 and were finally concluded in 2020, enable the operation of additional and longer trains on the line.

Source of labour.

During the Gold Rush, tens of thousands of Chinese immigrants, many of them were from the southern Chinese province of Guangdong (Canton), arrived in the United States. They arrived in the Kern River Valley in the late 1850s and early 1860s, and before being permitted to establish their own claims, they worked the mines for white claim owners. After a flood in 1862, the majority of miners left the region, but the Chinese remained.

Many immigrants who worked on the Southern Pacific railroad were veterans of the better-known Transcontinental Railroad, which connected the cross-country Union Pacific and Central Pacific lines at Promontory Summit, Utah, in 1869. Workers on the Transcontinental Railroad and Southern Pacific line braved environmental hazards like rock avalanches, cave-ins, and dangerous working conditions, mainly from using explosive black powder to blast through mountainsides for tunnels.

According to Hansen, “the job constructing the tunnels [for the Tehachapi Loop] was hazardous.” “Solid granite, decomposed granite, and soft earth were found. Therefore, incidents like cave-ins and other mishaps were frequent. On March 30, 1876, a charge of black powder burst too soon, burying 12 Chinese laborers. Three days later, an explosion in another tunnel caused by five kegs’ worth of powder resulted in nine fatalities and several injuries.”

After these catastrophes, 500 workers resigned. According to Hansen’s article, Chief of Construction J.B. Harris persuaded them to continue working by having a second crew follow the excavation team to put in temporary timber supports.

The workers had to deal with bigotry on top of these hazardous working circumstances. While white workers on the Transcontinental Railroad received room and board, Chinese workers were paid less and were required to provide for their housing and food. Additionally, they were disproportionately assigned the riskiest jobs, and many hundred perished in workplace accidents.

Leong Yen Ming was one of the best-performing people. Born in Say Yup, China, on March 13, 1858, he first worked on the Tehachapi Loop’s construction before switching to agriculture. He was also referred to as the Chinese Potato King and opened the first school in Bakersfield for Chinese kids in 1912. The highest purchase price in the county for that season was $10,000 in 1916 when he earned that amount for his entire crop.

Ming passed away at the age of 83 in 1941. Where his ranch formerly stood is now the Valley Plaza Mall, and the street it is on is named after him: Ming Avenue.

The 1998 ASCE monument adds that the Tehachapi Loop’s continued use nearly 150 years later “attests to the exceptional job of engineering and construction done by the two civil engineers and the Chinese laborers.”